How does the gut microbiome evolve as we grow older? Are certain microbes consistently enriched or depleted with age, and do these shifts correspond to functional changes in how our microbiome works?

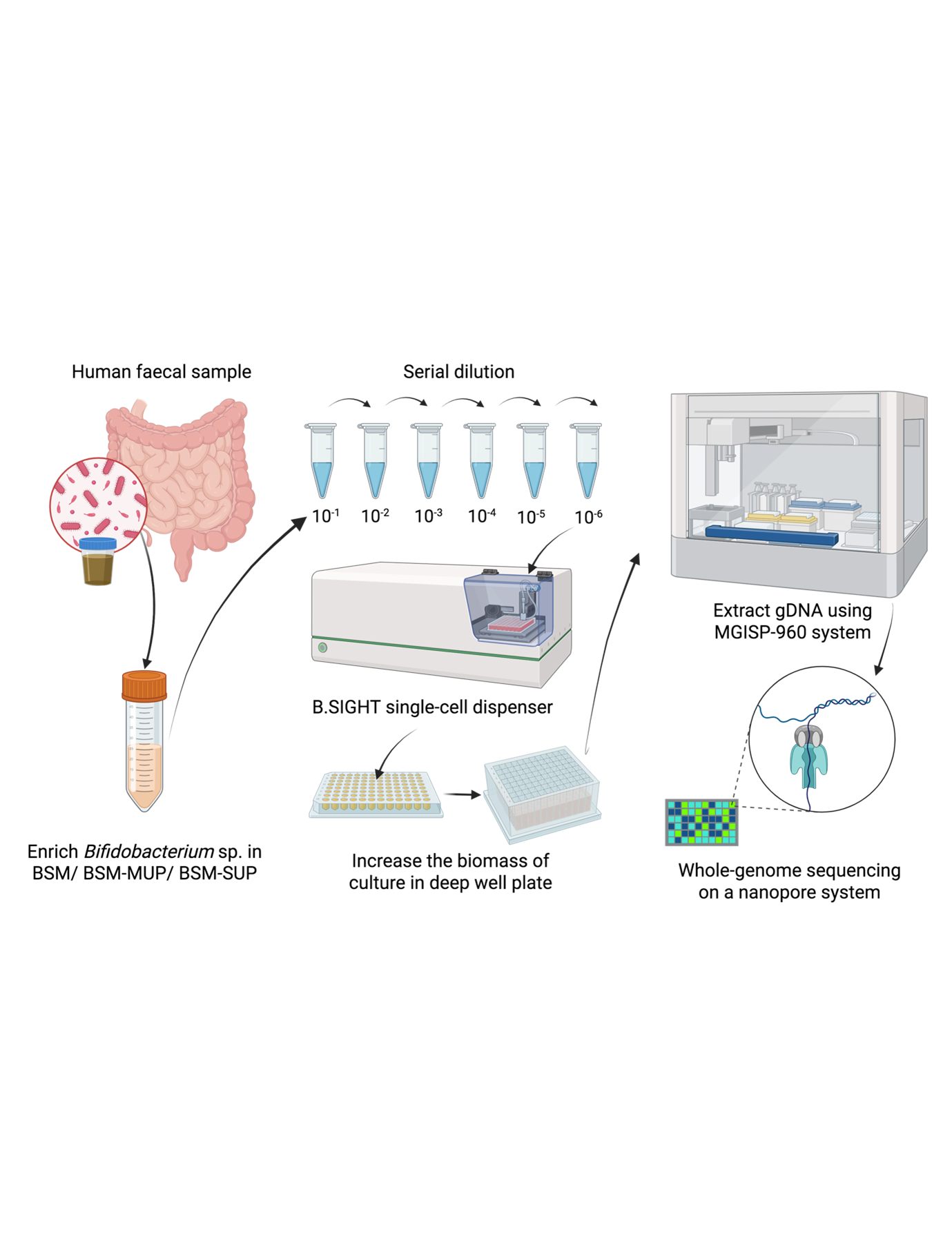

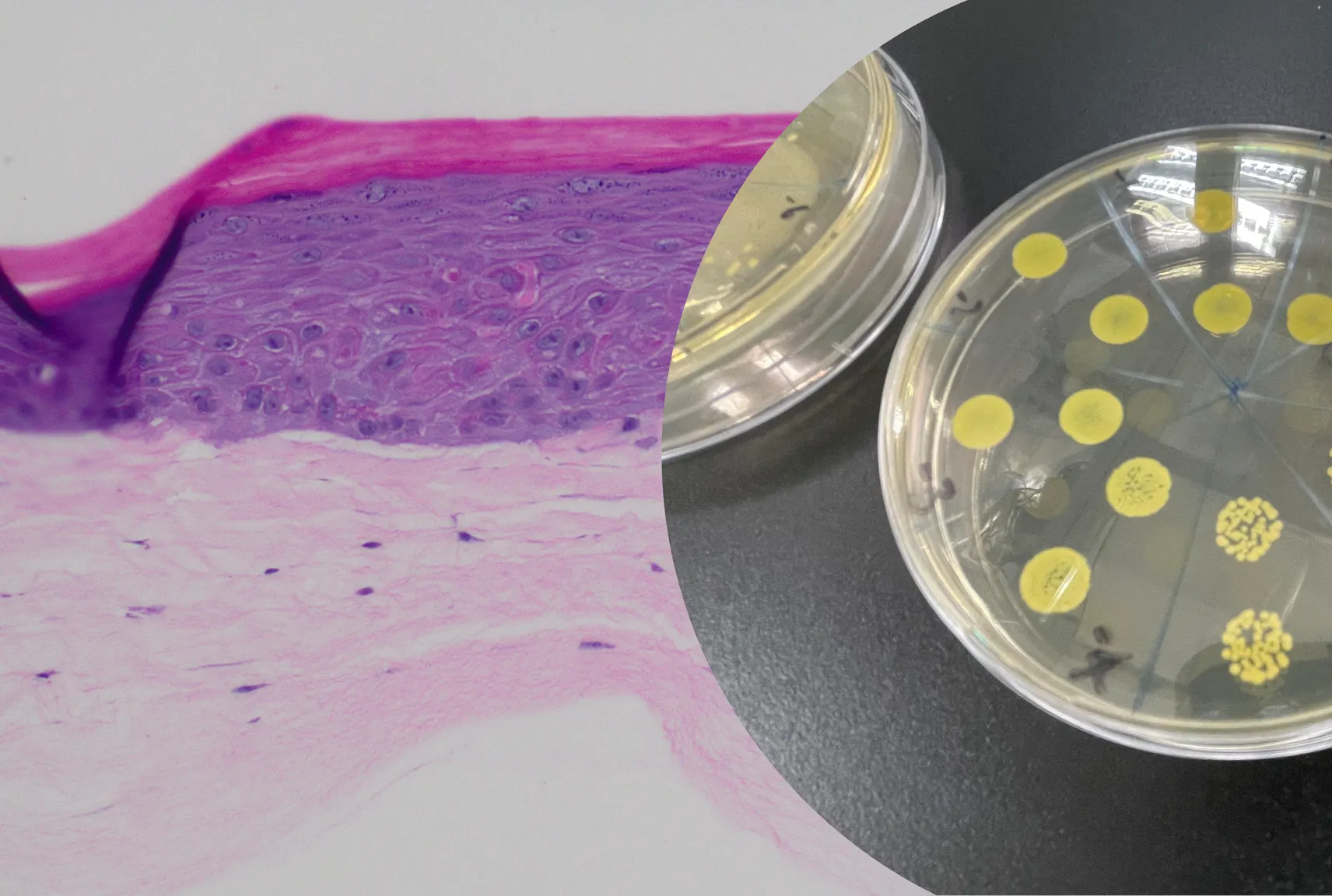

To address these questions, we performed shotgun metagenomics on one of the largest healthy aging cohorts in Asia with over 200 octogenarians. The results revealed a remarkably consistent pattern of microbial change across the aging spectrum and surprising functional expansions.

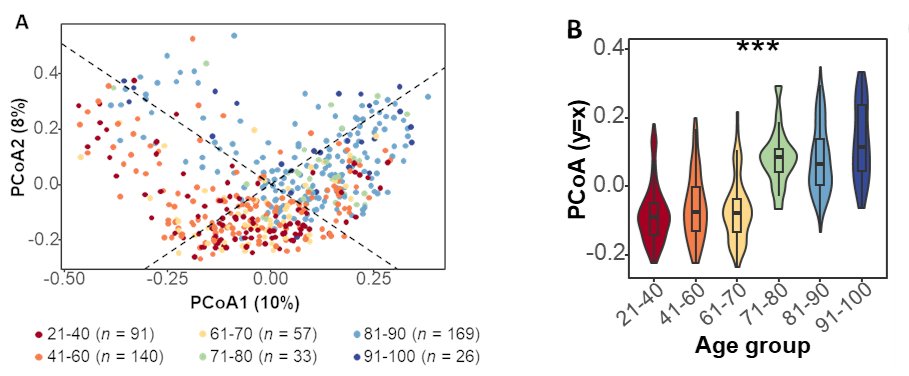

We found a progressive shift in microbiome composition with age, particularly along the y=x axis relative to the first and second principal components of variation.

This shift was driven by a reduction in microbial richness, evenness and Shannon diversity.

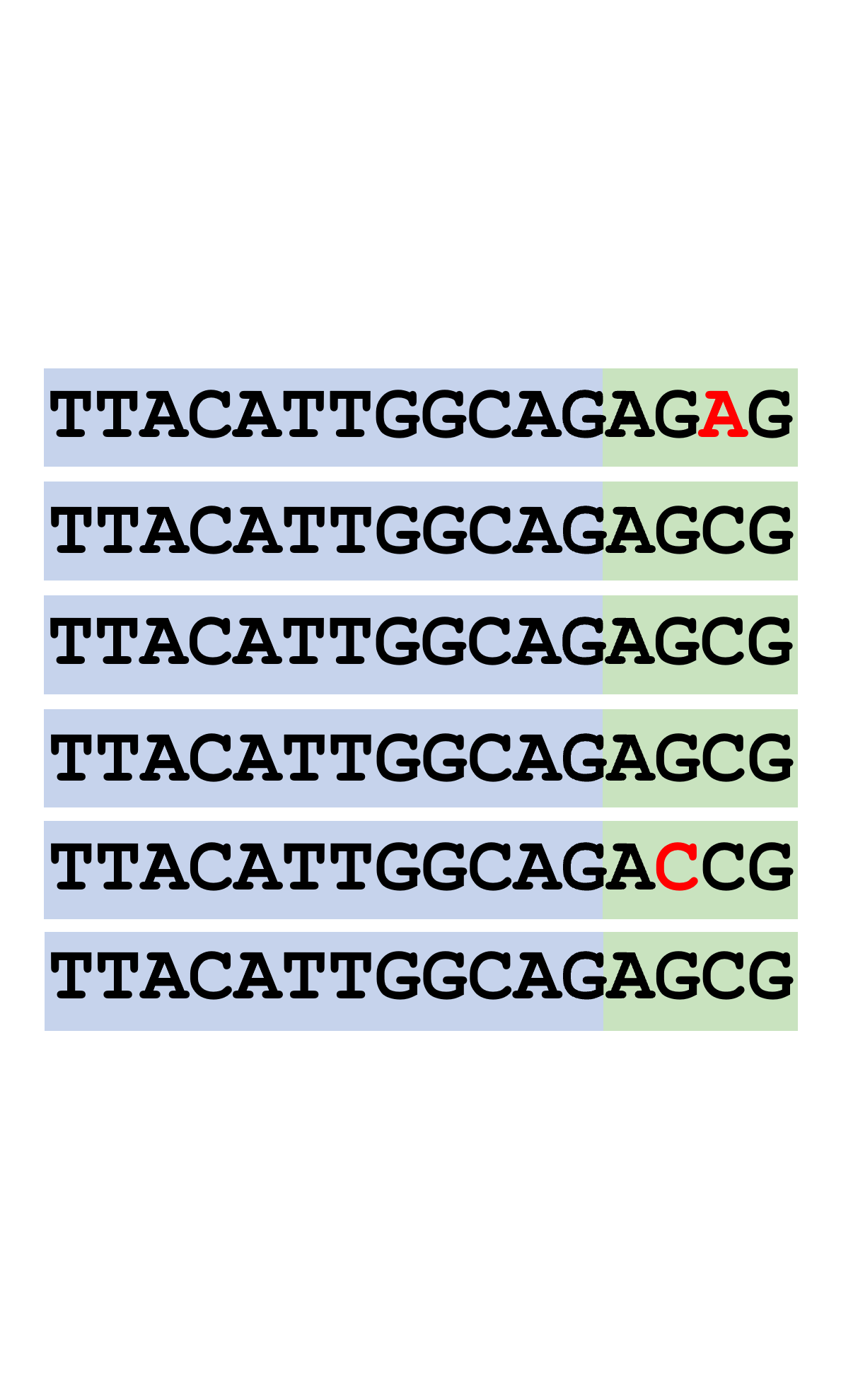

At the species level, some of the best-known butyrate producers — including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia — were depleted with age. These microbes are often linked to gut health and anti-inflammatory functions. At the same time, we saw enrichment of Bacteroides and Alistipes species, which appear to use an alternative metabolic route involving lysine to produce butyrate. In other words, while the usual butyrate producers decline, other microbes may step in using different biochemical pathways.

Further, at the microbial pathway level, we observed an expansion in the metabolic potential of butyrate synthesis pathways, particularly from L-lysine precursors. Congruently, (meta)Genome assemblies further confirmed this metabolic potential expansion where it showed many genomes of Bacteroides and Alistipes species harbor complete pathways for lysine biosynthesis. This suggests that the aging microbiome may not simply lose function — it may adapt by reorganizing its metabolic capabilities.

Surprisingly, these functional shifts were also recapitulated in mouse models of healthy aging. Although mice harbor a microbial community that is compositionally distinct from humans, we observed similar expansions in lysine-associated butyrate pathways. This suggests that the functional rewiring we see with aging may reflect a broader biological principle rather than a species-specific phenomenon.

Finally, the scale and depth of our cohort allowed us to uncover several associations between specific microbial taxa and host phenotypes relevant to healthy aging—insights that could help identify microbial markers or even modulators of long-term health.

A New Perspective on the Aging Gut

Our study, one of the largest gut microbiome analyses in Asian octogenarians, suggests that aging is not just a story of microbial loss.

Instead, it appears to be a story of restructuring and adaptation.

Some familiar microbes decline. New players rise. Metabolic routes are expanded. Community networks reorganize.

The aging microbiome may not just reduce in numbers and diversity — it recalibrates.

Understanding this transition could help us identify microbial signatures of resilience and, eventually, ways to support healthier aging trajectories.